Gisela of Kerzenbroeck’s Virtual Easter Celebration

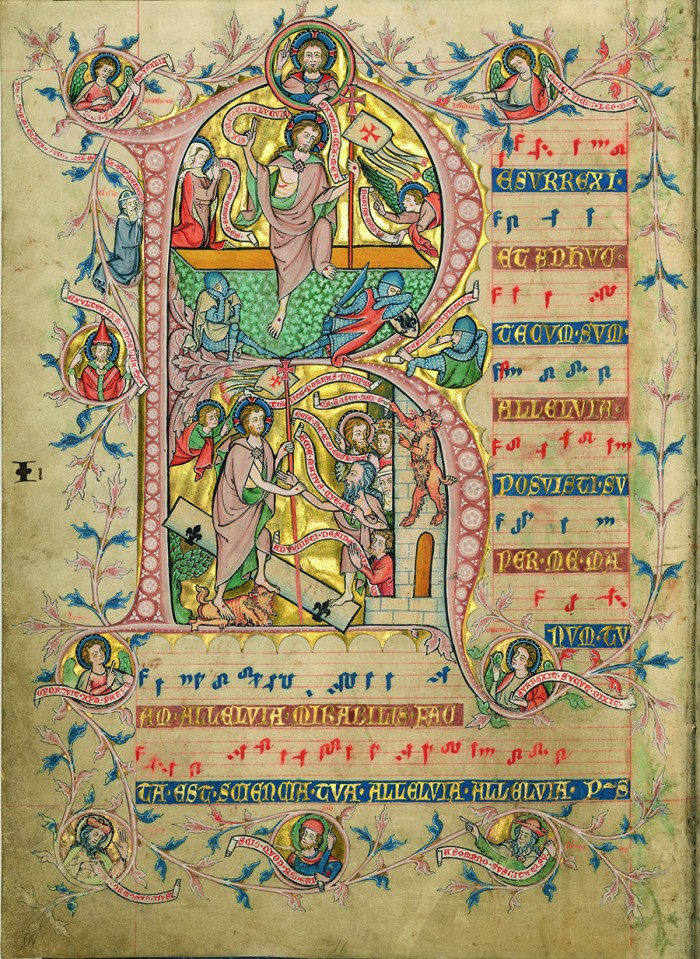

Take a good look at this stunning image of the Resurrection:

If you look carefully, you will see a nun kneeling at the top left. Her name –Gisle (Gisela) — is painted clearly but faintly in red, just by her head.

This is Gisela of Kerzenbroeck, a nun at the Cistercian monastery of Marienbrunn in Lower Saxony and the artist to whom the 52 paintings in this stunning manuscript are attributed.

A Gradual, a book containing the musical elements of the Mass, the Codex Gisle was made for use in the performance of the liturgy, in conjunction with a priest, at Marienbrunn.

Gisela’s name and role in producing the book, completed before the year 1300, were not recorded until many years later when someone made a note on the very first folio of the book:

“The venerable and pious virgin Gisela von Kerssenbrock wrote, illuminated, notated, paginated, and decorated this admirable book with golden letters and beautiful images in her memory. In the year of our Lord 1300 her soul rested in peace. Amen.”

It really isn’t surprising that the artist’s truly extraordinary talents were remembered and her name repeated long after her death. According to art historian Judith Oliver, a leading expert on this manuscript, Gisela was among the most gifted female artists of the Middle Ages.

In her book Singing with Angels: Liturgy, Music, and Art in the Gradual of Gisela von Kerzenbroeck, Oliver argues that it was a fellow nun and scribal collaborator at Marienbrunn who took the time to credit Gisela with this extraordinary work.

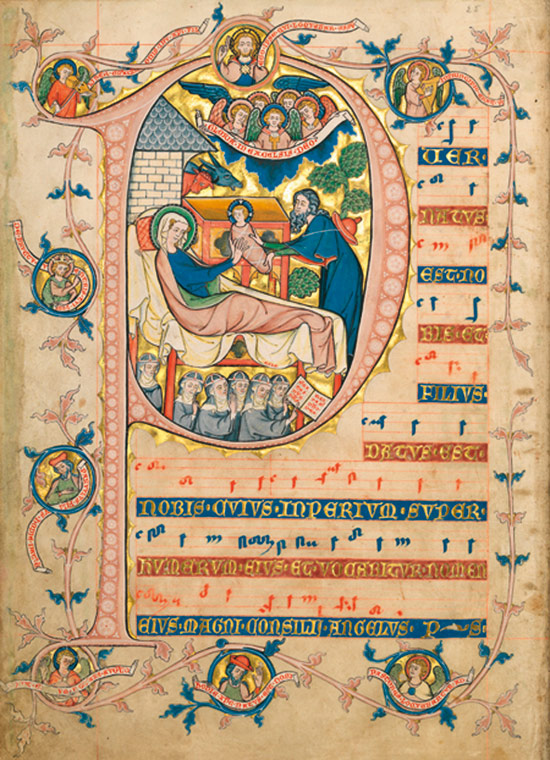

In a second portrait in the book, Gisela is shown leading the choir. You can see her there holding the service book, just below this image of the Nativity of Christ:

Again, Gisela’s name has been painted in in red, just above her head.

As leader of the choir (cantrix or chantress), Gisela would have held the important duty of overseeing the performance of the liturgy. In many monasteries, it was the cantrix who was in charge of the monastery’s book production, including books like this one, that were used in the performance of the liturgy. Some chantresses, like Gisela, were themselves scribes and illuminators. Gisela’s dual status as cantrix and scribe/illuminator makes perfect sense in the context of her monastic life.

But let’s go back to Gisela’s Easter illumination for just a minute.

There she kneels, participating virtually in a scene from which she is separated, not only by time, but also by physical space.

In the Middle Ages, religious women were often required to live in isolation — locked within their cloisters with the rest of their community or entirely alone — separated by an assortment of physical and spatial barriers from the rest of the world.

In her portrait, Gisela looks on, despite her temporal and physical distance from the action. There is a wall separating her, to be sure, but she manages to see right through the invisible door (or window) in it. With her brush, she has painted herself present, perpetually, at the Resurrection. Here she is, some 720 years later, still lifting her hands in prayer, still somehow present while distanced.

Religious women like Gisela have long been experts at making themselves present in places from which they are physically separated. In fact, in the midst of the current COVID-19 crisis, many communities of religious women have popped up virtually on television, in newspapers, and on Twitter, sharing their expertise with us as we live through our own version of claustration. Religious women, it seems, have a lot of experience with social distancing.

Sister Mary Catherine Perry, a Dominican nun in Summit, New Jersey, has offered tips about how to survive the pandemic lockdown.

Sisters from the community of Passionist Nuns of St Louis offered their advice on social distancing from behind the “grates and curtains” of their enclosure on television news.

Others are using technology to allow those inclined to be virtually present within their enclosures. The nuns of the Benedictine abbey of Minster, with its roots in the seventh century, have begun to livestream the Liturgy of the Hours from their cloister in Kent, England. Those who celebrate Easter can opt to look in on the midday office and the office of Compline, though far distant, via the nuns’ YouTube channel.

And there are many other examples.

This year, the major holidays of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam fall during this terribly difficult period of social distancing. As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, some of us have already become experts at the smooth hosting of the CyberSeder. Others will celebrate Easter virtually, with online egg hunts and dinner with family and friends on FaceTime. Still others will break the fasts of Ramadan with loved ones on Zoom.

Although her technology — paint, ink, and parchment — was obviously wildly different, it just may be that Gisela of Kerzenbroeck shared a similar impulse: to be present, though distant.

Wasn’t Marienbrunn a Bridgettine, rather than Cistercian, house? Her headress would also seem to confirm this.

Thanks for your comment! This is a different Marienbrunn. The one you are thinking of may be the Bridgettine house in Gdańsk (f. 1391). Gisela of Kerzenbroeck was a nun in Lower Saxony; her Marienbrunn was a Cistercian house founded in 1230. The name of the monastery was later changed to Rulle, which surely causes plenty of confusion. Crowns like the one Gisela and her nuns are wearing in the Codex Gisle were worn by religious women in many different types of community, including at houses that followed the Rule of Benedict and those associated with the Cistercian Order. There is a great photo of a very similar textile crown, probably worn by nuns at Rupertsberg (followers of the RB) in the twelfth century, in a recent article: Alexandra Gajewski and Stephanie Seeberg, “Art in the Monastic Churches of Western Europe from the Twelfth to the Fourteenth Century,” in Beach and Cochelin, eds. The Cambridge History of Medieval Monasticism in the Latin West (Cambridge, 2020), pp. 998-1026. The photo is found on p. 1013.

Lower panel shows the Resurrection of Lazarus!You can just catch a glimpse of his sister Martha on the right. Two resurrections. Lazarus to earthly life to show Jesus’s power when he looks up and asks God his father, then calls out to Lazarus “to come out” and tells others to unbind him. Lazarus will eventually die. Jesus’s Resurrection was to eternal life.

Thanks for your comment — so interesting! I hadn’t noticed the lower register (so focused was I on Gisela’s own position). And yes, now I see Martha there peeking out. I am so interested in these images of women in the Gospel stories and how they were understood and received by medieval religious women. More to the Mary and Martha dichotomy! Great observation, Regilind. Thanks!

For those interested Text is in Gospel of John 11:1-44

Again, it is Women who were the first witnesses of the Resurrection!

Thanks!!