The Enigmatic Guda: Sinner and Scribe (Part I)

What on earth would Guda make of it? A scientist (and a woman no less!) heading off from Ghent in a self-propelling vehicle carrying a bewildering device that emits a ray of light more intense than anything she could possibly imagine outside the context of visions of her God. And how much more terrifying — and perhaps also a little bit thrilling — that she is the reason for this unfathomable journey.

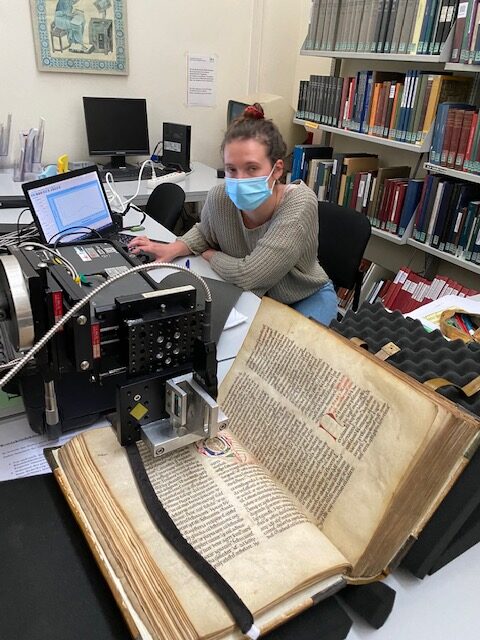

The scientist is PhD researcher Eva Vermeersch from the Raman Spectroscopy and Archaeometry Research Group at Ghent University. And the bewildering device is actually portable Raman spectrometer: a scientific instrument that uses light to identify specific materials by exciting and interpreting molecular vibrations. A laser beam is directed at a target material and the resulting light scatter is measured and used to determine the material’s “molecular fingerprint.” The Ghent Raman Group, headed by Professor Peter Vandenabeele, are world leaders in the in-situ examination of art using this technology.

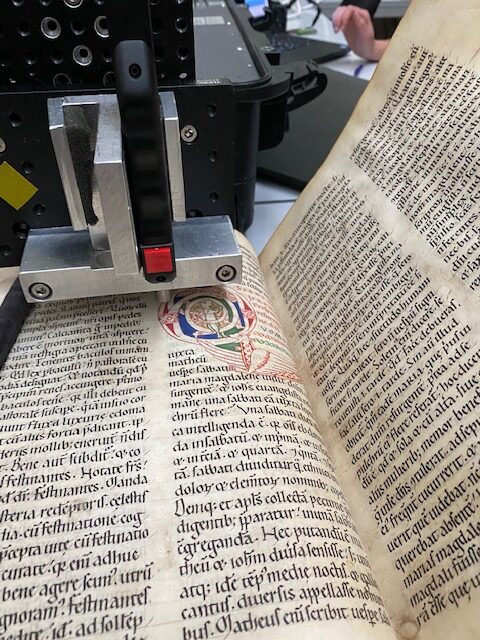

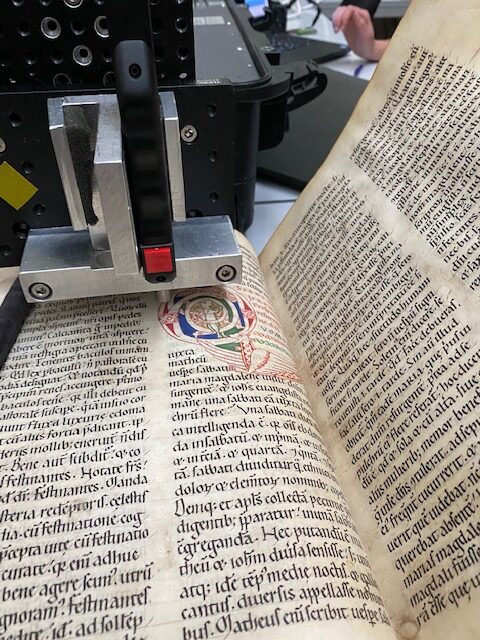

This time their destination is the library of the University of Frankfurt, where they will aim their laser at a beautiful homiliary (Frankfurt, Stadt- und Universitätsbibliothek Hs Barth. 42), a collection of sermons that Guda herself copied and painted some time around the end of the twelfth century.

We know that Guda is the scribe and artist behind the book because she tells us: “Guda, a sinful woman copied and painted this book.” And not only that. She painted a portrait of herself. You can have a look at her here:

By the way, just in case you are worrying…don’t! Firing a laser at an eight hundred year old manuscript may sound scary, but Raman spectroscopy will definitely not harm the manuscript. And trust me: Vermeersch really know what she is doing!

If all goes to plan, the Raman analysis in Frankfurt will identify the pigments that Guda used for this and the other decorations in the manuscript. Perhaps ochres for the red and yellow. Malachite for the green. And just maybe precious lapis lazuli for the blue.

I first became acquainted with Guda and her homiliary a few years ago while I was working on another really exciting project. Together with a team of scientists associated with the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, I worked to make sense of a strange and unexpected discovery: ground lapis lazuli — a precious blue stone — embedded in the dental calculus of another medieval German religious woman from roughly the same period.

What we concluded was that this woman had likely been a highly skilled artist, a painter of fine manuscripts who repeatedly put her paintbrush in her mouth. If you didn’t read about that discovery at the time and you want to hear more, you can find the article that we published in Science Advances, or the report of the story in the New York Times or on CNN. It created quite a stir!

In making the point in the press that twelfth-century women are known to have produced manuscripts at the highest level, we turned to Guda as an example. Her self-portrait made an ideal visual to accompany the story in news outlets like the BBC and National Public Radio.

But Guda has her very own story to tell. Who was she? A nun? A Penitential Sister? Where did she live and pray and work? Why does she call herself a peccatrix mulier (a sinful woman)? As the team’s lead historian, I have a few theories about this, but you will have to wait for a future post (or the academic journal article) to hear those! If calling herself a peccatrix mulier signals humility, then what are we to make of her decision to tell us her name and take credit for her artistry? Or of the startlingly bold move — without precedent in the medieval West — of showing us her face?

And what if she used lapis lazuli pigment — as valuable as gold — to paint that self portrait? Not exactly in keeping with gendered assumptions about female humility and invisibility in the Middle Ages.

We’ll just have to wait for what Vermeersch and her spectrometer discover!

Almost as amazing is that my daughter Professor Alison Beach arranged for this incredible cooperation of historians and scientists!