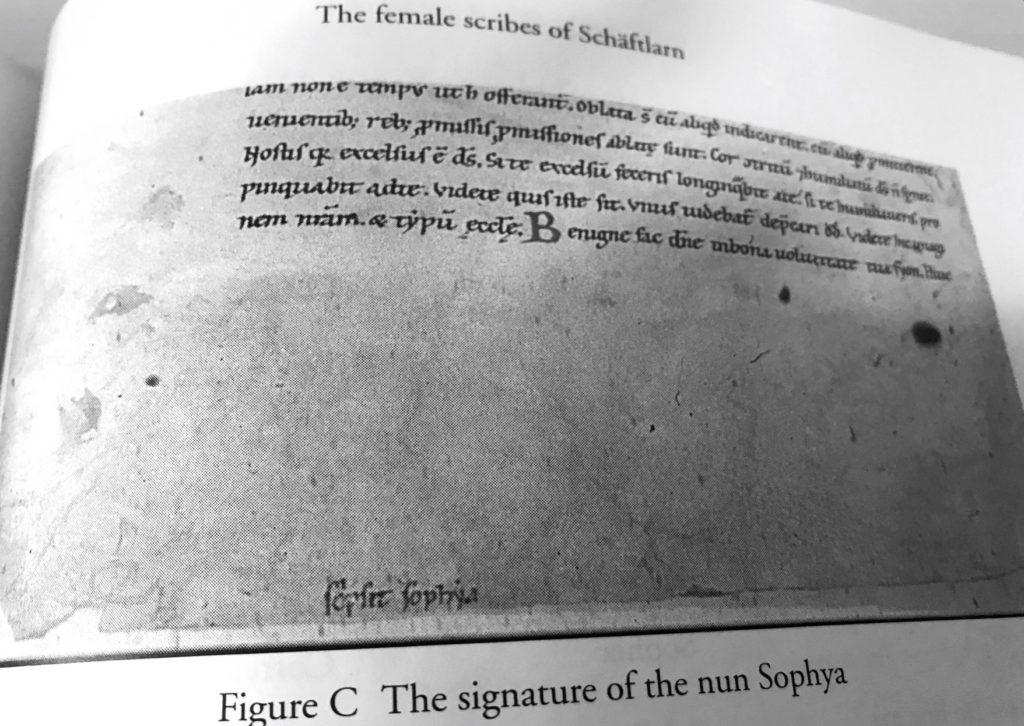

Scripsit Sophya

When you are looking for a medieval female scribe, it doesn’t get any better than this: “Scripsit Sophya” — Sophia wrote [this]! It really doesn’t. You can see Sophia’s scribal signature here, right at the bottom edge of the parchment:

Imagine if a bookbinder, either Medieval or more modern, had trimmed that parchment just a bit more… This signature would have been lost!

This manuscript, Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek Clm 17052, is the first of a three-volume copy of St. Augustine’s commentary on the 150 Psalms in the Hebrew Bible. This and other biblical commentaries were medieval “bestsellers” — staples of twelfth-century monastic libraries, where they served as tools and companions for biblical study. The third volume of the set, which was completed before the year 1160 or so, is lost.

Way back, when I was interviewing for my first teaching job, a prospective colleague at my campus job talk was not convinced. What, he asked, if this was really the work of a male scribe with a super-clever pen name: Wisdom! After all, “sophia” is the Latin word for wisdom. “Wisdom wrote this!” — which makes so much more sense than the simple reality that a female scribe with the very common name Sophia, attested repeatedly at her own monastery in the twelfth century, copied these books! Um, no. You won’t be surprised to hear that I didn’t get that particular job.

I don’t tell this story to complain, really, but to suggest how far we have come in the past twenty years. The kind of a priori assumptions that lead to such an Ockham’s Razor-violating suggestion really have shifted. And this has been the result of a number of medievalists looking carefully and documenting the work of female scribes across Europe and throughout the Middle Ages.

So how do we know if a scribe was a woman? Sophia made that easy for me by identifying herself — just like Sister Margareta at Admont did. This is the best-case scenario: a scribe names herself and I can then examine her hand(writing) and go looking for her work in other manuscripts. Sophia, for example, also copied Augustine’s commentary on the Gospel of John (Munich, Clm 17054). I will be on the hunt for some examples of Margareta’s work soon, too!

One thing to keep in mind is that medieval scribes, both female and male, strove for uniformity, and medieval book hands really do not exhibit the same degree of self-expression that modern handwriting often does. There is nothing “female” or “feminine” about a particular medieval hand — you just can’t tell. In other words: no hearts over the I’s to tip you off… Medieval book hands are just not gendered. That would make things easier!

Female scribes also had a penchant for collaboration, and in some cases we can identify additional female scribes who worked particularly closely (alternating work, say, every few lines) within the individual units (called quires or gatherings) that make up a particular book. The nuns of Admont were great collaborators in the scriptorium, and they seem to have worked really hard to use the same letter forms and abbreviations to create a unified look for each page.

Sophia, on the other hand — and maybe this will surprise you! — collaborated closely with a male scribe called Adalbert, who also identified himself in a scribal signature. The nuns of Admont, where life was organized according the the sixth-century Rule of St. Benedict, were cloistered (locked within their buildings with strict and elaborate rules for opening the doors). We have no indication for that practice at Sophia’s very different community: Schläftlarn. Schäftlarn was Premonstratensian, a new type of religious community in the twelfth century with its own rule and customs. At least at Schäftlarn, there seems to have been a more relaxed approach to contact between the women and men who pursued religious life there! The books that survive from the twelfth-century community attest to that contact.

And sometimes scribal self-identifications come when you least expect them. This past January, my husband David and I visited the Benedictine monastery of Eibingen on the Rhine (which traces its roots back to none other than the famous Hildegard of Bingen) to taste and buy for an upcoming tasting of wine produced by nuns. I may or may not have bragged a bit about my work on medieval female scribes to Sister Thekla, the master winemaker for the monastery. And who was working the cash register in the gift shop at that time and overheard the conversation but Sister Michaela, the monastery’s very own nun-scribe? Scripsit Michaela! I’d like to see anyone explain that one away!

(whose lovely cards are available in the Eibingen gift shop!)

Megan Hall just alerted me to your new blog and I’m enjoying it! I’ll recommend it to my younger sister who majored in Medieval Studies as an undergraduate and to her husband who was fascinated by the “blue teeth” article in the NY Times.