Was “anonymous” a woman?

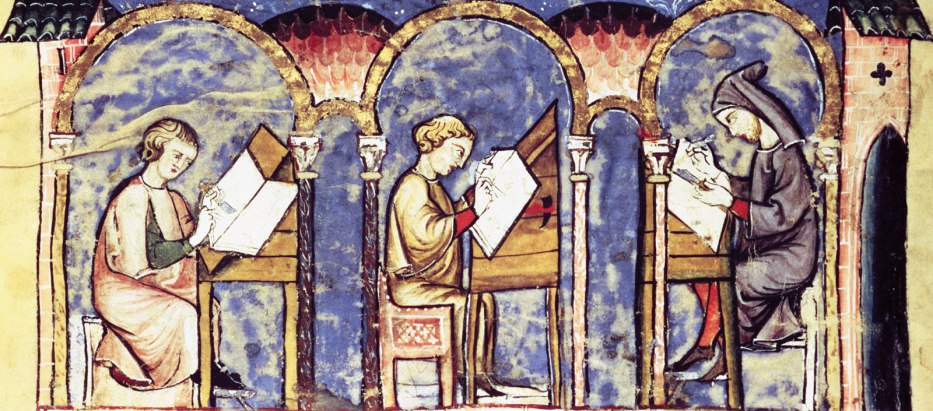

Do a thought experiment with me for a second. Close your eyes and call to mind a scriptorium (a space of book production) in a medieval monastery. Imagine the setup — from the lighting, to the desks, to the materials set out on them, to the individuals at work with writing instruments or brushes in hand. If you get really excited, google “medieval scriptorium” when you open your eyes and scroll down through the images (both medieval and modern) that are displayed. It’s pretty much monks all the way down.

Now, a medieval historian, and particularly one familiar with the various practices of book production in the Middle Ages (there are many of us!) may well shout rude things at the TV when she sees elaborate workshops filled with monks diligently writing and painting to the light of candles dripping with wax (no, no, come ON — all those candles?? — in a scriptorium?? — with all of that super flammable stuff!?? and why are those eighth-century monks dressed in Franciscan habits??). But these are the sorts of images that tend to shape and dominate the popular imagination. And if I am being honest, they sometimes also shape the scholarly imagination, especially in view of the dominance of monks in medieval portrayals of book production. When handed a medieval manuscript with no known producer, most of us still first imagine a monk as scribe or illuminator.

One of the key criticisms of the astonishing media coverage that followed the release of the Science Advances article on the medieval woman with lapis lazuli trapped in the matrix of her dental calculus (Radini et al. 2019) was that the reporters were failing to convey the fact that this discovery added incrementally (an exciting increment, to be sure!) to what many of us have been saying for decades: medieval women were actively engaged in producing books in the monasteries of Western Europe, even at the highest level of skill and material. When confronted with a new (to them and to many of their readers) image — a medieval woman with a paintbrush in her mouth, hard at work on a deluxe manuscript — the reporters got excited. And why not? It is an exciting discovery that my colleague Anita Radini made under the microscope, and a really good interdisciplinary detective story that brought together archaeologists, physicists, and medieval historians in (at least) three countries. And as Jo Livingstone concluded in her piece in The New Republic on the twitter controversy over media coverage, “Among many, the chief lesson of the nuns’ teeth must be that women and their work still matter, a lot, to people today.”

I am going to launch this new blog with a series of posts that highlight some the work of female scribes and book painters in the Middle Ages. A handful of them (really, not too much more than a handful…) identified themselves in a sort of scribal signature called a colophon (more on that soon!); some are identified by the authors whom they helped to produce their writings. In some cases, we can find examples of their work, and for others we have only a name. Importantly, the vast majority of medieval books were produced with anonymous hands. So when you retry that thought experiment, be sure to keep in mind that many of those anonymous hands may have been those of a woman!

Hi, Alison,

I just found this. Wonderful!! What a great contribution!

Thank y0u for doing it.

Beverly

Thanks, Beverly!